How did employer-sponsored health insurance come to dominate in the delivery of health care in the U.S.? And could there be a better way to offer high-quality, cost-effective care? Unions have led the way on both of these questions.

How did employer-sponsored health insurance come to dominate in the delivery of health care in the U.S.? And could there be a better way to offer high-quality, cost-effective care? Unions have led the way on both of these questions. In the era of COVID-19, it’s more important than ever that we understand our history and work together toward an inclusive system for all.

In the beginning

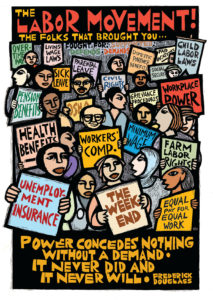

Going back to at least 1798, mutual aid societies, unions, and government initiatives in the U.S. aimed to help sick and injured workers. In that year the U.S. Marine Hospital Service was established by deducting 20 cents a month from seamen’s wages. Hospitals were built under this service at several U.S. sea and river ports to treat all classifications of marine workers for sickness and injuries. Sponsored by an Act of Congress, the Service eventually evolved into the U.S. Public Health Service, a vital center for research and public health policy.

Beginning in the 1870s, employers in heavy industries such as railroads and mining started taking deductions from workers’ pay to provide company doctors to care for injured or ill employees. “Industrial medicine” was focused on company priorities to keep workers on the job. Until the Workers’ Compensation system evolved on a state-by-state basis beginning with Wisconsin in 1911, there were no standards for the provision or quality of care.

The Granite Cutters Union was the first to set up a sick benefit program for members in 1877. Many programs sponsored by unions and mutual aid societies of this era offered an income benefit rather than direct medical care. Medical practices and systems were still in their infancy, and sometimes viewed with distrust and fear by the public. Advances in medical care and increased regulations helped to change attitudes at the turn of the century, and in 1913 the International Ladies Garment Workers Union created the first union medical services program.

Medical care not associated with the workplace during this early period was generally arranged and paid for directly with doctors or hospitals. It wasn’t until 1929 that the precursor to Blue Cross prepaid hospital insurance was initiated by a group of Dallas teachers who contracted with Baylor University Hospital to provide hospitalization services. Separately, a California physicians’ group, with help from an official who had worked on New Deal era programs, organized prepaid plans for physician services that came to be known as Blue Shield in 1939. From these beginnings, prepaid health insurance steadily gained in popularity, with labor unions providing a push forward.

Expanding coverage

A big change in health care delivery occurred in the World War II years, and a major catalyst for the change was labor unions. In order to stave off inflation associated with wartime labor shortages and scarcity, the government put wage and price controls in effect. Unions, a growing and powerful voice for working people, pushed companies to fund health care benefits as a way to provide improvements in lieu of wage increases.

A big change in health care delivery occurred in the World War II years. Unions, a growing and powerful voice for working people, pushed companies to fund health care benefits as a way to provide improvements in lieu of wage increases.

Companies were initially resistant, and a wave of postwar strikes included demands for health benefits, such as a 113-day strike by UAW workers at General Motors that started in 1945 and spilled into 1946, and a bitter confrontation between the United Mine Workers Union and mine owners in 1946. Eventually, a 1954 Internal Revenue Code ruling permitted companies to deduct the cost of benefits as a business expense, thus tempering the fierce resistance from business interests. The connection between health insurance and employment was forged.

A better way?

But even as the connection between health insurance and employment became common, unions and some legislators advocated for a more inclusive and comprehensive system. Michigan Congressman John Dingell Sr. co-sponsored a bill calling for national health insurance in 1943, and President Truman supported national health insurance in his 1948 state of the union address. United Auto Workers (UAW) President Walter Reuther served on Truman’s Commission on Health Needs of the Nation, and Reuther went on to form the Committee of 100 for National Health Insurance in 1968. Reuther had long viewed the right to good health care as a basic human right.

An encounter Reuther had while in the hospital recovering from a 1948 assassination attempt left a big impression on him. Reuther befriended a young man who had been paralyzed for nine years, but was starting to see improvements with hospital treatment. One day, he saw the young man crying and asked the attending nurse if there was a setback. It turned out the only setback was that the young man had run out of money and would no longer get the treatments that were finally reversing his long-time paralysis.

In cruel contrast, a story in the press trumpeted the extreme lengths that General Motors President C.E. Wilson was taking to cure a prized bull he owned. An x-ray machine was flown to Wilson’s farm so not to put stress on the bull. When the machine arrived it was discovered that the power lines couldn’t deliver the volume of energy needed, so Wilson had a special high-voltage line installed. The best medical specialists were summoned to provide treatment for Wilson’s bull, yet the young man Reuther met during whirlpool treatments was destined to suffer permanent paralysis because he couldn’t afford the care that was helping him. Reuther was galled by the juxtaposition of these situations.

Unions: advocates for the collective good

In the years that have followed, unions have fought for improvements for their own members and alsofor society at large. There are practical and philosophical reasons why unions choose to do both. On the practical side, collective bargaining provides a path for unions to win immediate gains for the workers they represent. Keeping and growing those gains is impacted by broader economic, social and political forces, so it makes sense for unions to engage in issues beyond the workplace. However, standing up for the collective good is a core union principle, not simply a practical strategy to protect union gains. This principle helps explain why unions push for more than what is in their direct self-interest.

In the years that have followed, unions have fought for improvements for their own members and alsofor society at large. There are practical and philosophical reasons why unions choose to do both. On the practical side, collective bargaining provides a path for unions to win immediate gains for the workers they represent. Keeping and growing those gains is impacted by broader economic, social and political forces, so it makes sense for unions to engage in issues beyond the workplace. However, standing up for the collective good is a core union principle, not simply a practical strategy to protect union gains. This principle helps explain why unions push for more than what is in their direct self-interest.

Even as unions fought tooth-and-nail for employer-paid health care benefits in the post World War II years, they also supported calls for national health insurance. In 1957, the 14 million member AFL-CIO declared the fight for national health insurance to be a top legislative priority. Collective bargaining had already won health insurance benefits for thousands of union members, but the principle of fighting for the collective good propelled a major charge for a national program to address the health needs of all. Conservative political leaders joined forces with the American Medical Association (AMA) to fiercely oppose national health care, claiming it would be too costly for taxpayers and lessen the medical establishment’s control over practices and costs.

Labor activism scores Medicare and Medicaid win

The struggle that led to the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 wasn’t easy or quick. The same conservatives and medical organizations opposing national health care worked to defeat the proposals more narrowly targeted to the elderly, disabled and low-income individuals. Legislation began appearing in the late 1950s and it was thought to stand a better chance of passing than full-out national health insurance for a couple of reasons. It wouldn’t cost as much as a program covering everyone, and furthermore, a growing elderly population was experiencing distress. The number of elderly shot up from 3 million in 1900 to 12 million in the 1950 census count. Two-thirds of the elderly had annual incomes under $1,000 in 1950 – about $10,000 in today’s dollars, and only one in eight had health insurance.

Early on, labor unions were at the forefront of pro-Medicare and Medicaid movement. Union retiree organizations banded with other supporters to mount an all-out offensive to build popular support through the National Council for Senior Citizens (NCSC), including years of conducting town halls, media campaigns, testifying before Congress, and pressuring the political establishment. In 1964, 14,000 retirees arrived on busses to the Democratic National Convention to push President Johnson into action. Some of their placards read, “Senior Citizens Vote, Remember Medicare,” and “Our illnesses burden our families.” It took years of this type of activism, and finally, on July 30, 1965 the Medicare and Medicaid programs were signed into law.

It would be difficult to overstate how much the Medicare and Medicaid programs have improved the lives of millions of Americans. The basic health and well-being provided through the provision of health care enables more productive individuals, and as a result, a more productive society.

It would be difficult to overstate how much the Medicare and Medicaid programs have improved the lives of millions of Americans. The basic health and well-being provided through the provision of health care enables more productive individuals, and as a result, a more productive society. This applies not only to working age individuals, but also to the elderly who still have so much to contribute to society when they are healthy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicare and Medicaid have provided a vital social safety net for both young and old.

Practical and principled action

A common phrase heard at union gatherings is “an injury to one is an injury to all.” Perhaps this phrase explains how practical actions and values can converge. Today, for example, as labor unions overwhelmingly support the Affordable Care Act (ACA), there are both practical considerations and important principles that influence their actions. Fundamentally, the ACA has kept our medical system from imploding under the weight of bloated costs and inefficiencies. On a practical level, the ACA has ensured there’s a medical system in place to deliver the care negotiated by unions for their members. But the union principle of standing up for the collective good is the over-arching value guiding today’s union activists to support expanding coverage to those who need it.

Back to the future

The critical role of labor unions in establishing health insurance benefits and broader health policies is not in dispute. But how are unions going to continue their advocacy for working people at the present time? As job losses mount and with COVID-19 numbers on the rise, the prospect of crippling medical bills from this killer virus is a terrifying reality for workers no matter their union status. This is precisely the time to act from the principle of the collective good.

As job losses mount and with COVID-19 numbers on the rise, the prospect of crippling medical bills from this killer virus is a terrifying reality for workers no matter their union status. This is precisely the time to act from the principle of the collective good.

The forms of assistance newly unemployed workers are eligible for varies widely across states, and there’s plenty of contentious political fighting about health care that seems to just add more confusion into the mix. Unions have faced these tough times before, and there’s no less fight in American workers now then there’s been in the past.

These actions can help right now:

Expand Medicaid. Thirty-nine states have already acted to expand Medicaid eligibility utilizing federal ACA dollars. All the states need to get on board so that the millions losing their health coverage due to COVID-19 job losses will have a basic safety net. Among the top 10 states with the highest number of uninsured adults, all but two are states without expanded Medicaid coverage.

Help workers afford COBRA benefits. Laid offworkers can keep their employer-sponsored health insurance for 18 months if they can afford to pay for it.There have been calls for federal government assistance so unemployed workers can keep their coverage when they can least afford to pay for it.

Strengthen the ACA. Expanding access to the ACA’s subsidized insurance market can be a virtual lifeline for the newly unemployed. “Taking steps like these to help people get access to health care during a pandemic shouldn’t be controversial, it should be common sense,” says Senator Patty Murray, who sits on the Senate Health Committee. Yet there is controversy about this, and unions are allied with those pushing to strengthen and extend the ACA.

Build strong unions to assure a health care system for the long haul that puts human needs first. As the issue of affordable, quality health care continues to be top of mind for many people in this country, strong labor unions will build on the principle of collective good. This is how we can honor the past and create a better world for the generations to come.