Getting health policy on track to address obesity will have a major impact on overall health and health care costs – especially as COVID-19 accelerates this already present trend. And getting this health policy right requires going beyond the prescription of individual “willpower.” The science of how foods are engineered and the overall food landscape play an incredibly large role in determining the foods we end up consuming. Health policy needs to reflect these big picture elements along with encouragement to individuals to eat a healthy diet.

The stakes are high. Steven Gortmaker, a senior author of the study, zeroed in on why its findings are so troubling: “Obesity, and especially severe obesity, are associated with increased rates of chronic disease and medical spending, and have negative consequences for life expectancy.” Indeed, there’s little debate that carrying excess weight negatively impacts health.

The harder questions to answer: why are obesity rates going up so dramatically, and why is it so hard to lose weight? These questions are often emotionally charged for individuals. Social stigma associated with carrying excess weight often results in discrimination and unfair treatment in the workplace, education, and health care settings. At the core of this stigma are faulty assumptions about personal failings and lack of individual willpower.

“Just giving people nutrition advice won’t be enough. We need to advocate for policy initiatives and support people’s needs. This is a social justice issue. And we’re living it right now.”

Ashley Gearhardt, U-M FAST Lab

The reality is that obesity is much more complex than calculating calories consumed minus calories burned. Physiological and social factors are part of the complexity. The problem is much bigger than individuals exercising self-control. “Just giving people nutrition advice won’t be enough. We need to advocate for policy initiatives and support people’s needs. This is a social justice issue. And we’re living it right now,” says Ashley Gearhardt of the Food and Addiction Science and Treatment (FAST) Lab at the University of Michigan.

The food landscape

Efforts to educate the public about healthy food choices and good exercise habits are not in short supply. The trouble is, those efforts exist within a food landscape in the United States that offers plenty of cheap, high calorie foods engineered to appeal to our cravings for salt, sugar, and fat. It’s hard to avoid these foods – you find them on supermarket shelves, displays at the drugstore checkout counter, gas station mini marts, and in restaurants of every type. Healthier choices can also be found, albeit in less abundance and with less mass marketing appeal.

Engineering for obesity

Ultra-processed foods trigger over-eating. A study conducted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) found that independent of nutritional makeup, and even perceptions of taste or being satiated, people eat more calories when offered ultra-processed foods versus whole, unprocessed foods. Ultra-processed foods contain things such as added sugars, fats, and chemical preservatives that the brain’s pleasure receptors quickly get used to and crave in higher quantities. “This is not about willpower – we’re living in a manipulated food environment,” says Gearhardt of the U-M FAST Lab. Because these foods are cheaper, more convenient, and have a longer shelf life, they now account for more than half the calories Americans eat.

Ultra-processed foods contain things such as added sugars, fats, and chemical preservatives that the brain’s pleasure receptors quickly get used to and crave in higher quantities. “This is not about willpower – we’re living in a manipulated food environment,” says Gearhardt of the U-M FAST Lab.

Advertising heavily promotes the bad stuff. Of the $10.9 billion spent on television ads for food in 2017, 80 percent was for the unhealthiest offerings such as fast food, soda, candy and unhealthy snacks. A report from the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity found that the ads targeted young people, and Black and Hispanic consumers. Teenagers viewing fast food ads showed greater activation of the reward center of the brain than when viewing other types of ads. “The teenagers that are showing this greatest reward activation of the brain seem to be at greater risk in gaining weight over time. It’s hard for people to defend against because it’s not a conscious process,” says Gearhardt.

And beverage industry giant Coke came under intense criticism for sponsoring “science-based” messaging that people should focus more on exercise, and less on their eating and drinking habits in order to maintain a healthy weight. Most health experts now acknowledge that food intake, not exercise, is the more significant factor for weight loss.

We eat out more, and consume bigger portions when we do. Americans spend more of their food dollars on eating out than they do on picking up groceries and cooking at home. Over time, restaurant portions have been supersized not just at fast-food spots, but non-chains as well. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says the average restaurant meal is now more than four times larger than it was in the 1950s. Choosing to not overeat is an uphill endeavor when presented with a typical restaurant plate of food.

The consumption of sugary beverages, while declining in recent years, still represents a tremendous volume of sugar consumption. The typical 12-ounce can of soda contains 7-10 teaspoons of sugar, and on any given day, 60 percent of children and 50 percent of adults say they drink a sugar-sweetened beverage. Drinking these nutritionally empty calories doesn’t lead to eating less food, and in fact the opposite may be true. Dozens of studies consistently show that soft drink consumption is linked to increased calorie intake. Aside from weight gain, sugary beverages increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic diseases.

Shaping social policy and practices to impact obesity at the source

While individuals ultimately choose the food and drink they consume, the broader food environment in which those choices are made can impact behaviors.

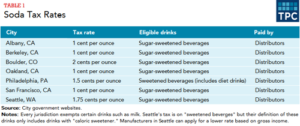

Soda taxes. Seven U.S. municipalities have instituted soda taxes, taxing sugary drinks anywhere from 1 to 2 cents per ounce. Philadelphia was the first large city to do so in 2017, with a 1.5 cents per ounce tax that was used to fund an ambitious early childhood education program. Studying data from the Philadelphia area, researcher Christina Roberto called the soda tax “a no-brainer.” Roberto co-authored a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association(JAMA) that showed a 38 percent decrease in sugary drink sales, even after accounting for increased sales outside the city limits.

But the beverage industry strongly opposes soda taxes. They successfully lobbied Michigan legislators to ban taxing soda in 2017, and convinced California lawmakers to ban them in any municipality other than the four cities already having one in place in 2018. Cook County, which includes the city of Chicago, repealed its soda tax in 2017, after the American Beverage Association was successful in characterizing the tax as a “money grab that has nothing to do with public health.” American Heart Association CEO Nancy Brown countered by saying the Cook County repeal “protects beverage industry profits at the expense of kids and families.”

Reducing restaurant portion sizes and defaulting to healthier foods. Perhaps the assumption that consumers want large portions of food loaded in fat, sugar, and calories is something of a chicken and egg proposition. Restaurants can reverse the “supersize” trend by stealthily making small, gradual reductions in portion sizes, and sugar and fat content. Changes are indeed occurring as some restaurants now offer smaller sized beverage containers and kids’ meals with a reduced portion of fries. These types of actions on the part of beverage producers and restaurants may be more effective than simply posting calorie and nutrition information.

Incentivize production and consumption of foods with less sugar, salt, and fat. While people want the freedom to eat whatever they choose, attitudes can change if people understand that addictive ingredients insidiously make us reach for the wrong choices. Social policies and raising public consciousness can tilt the food landscape in a healthier direction.

“From a policy perspective, prevention is the way to go,” says Zachary Ward, a Harvard public health specialist and co-author of the obesity projections study. “Children aren’t born obese, but we can already see excessive weight gain as early as age two. Changes in the food environment are needed at every level – local, state and federal.”